A Short History of the Mechanics' Institute of San Francisco

by Taryn Edwards

What is a Mechanics' Institute?

Mechanics' Institutes in general were the offspring of the industrial revolution. They were created in Scotland in the 1820's with the objective of providing technical education to those for whom a traditional university experience was unattainable.

The concept spread like wildfire throughout the English speaking world and at its pinnacle there were some seven hundred Mechanics' Institutes in England alone[1].

Typically, Mechanics' Institutes offered their communities vocational and technical "hands on" classes, lectures on science, technology and the humanities, a library that supported the Institute's educational aims, and recreational opportunities that encouraged camaraderie. Such a facility was greatly needed in Gold Rush era San Francisco.

Why was the Institute founded?

In 1848 San Francisco had roughly 800 people. By 1852 the population had mushroomed to 34,000 with over 100,000 a year still coming. Most of them left the city to try their hand at mining but the gold had gotten harder to find. The city began to experience an influx of former miners returning to the city — exhausted, depressed, and often without enough money to support themselves.

The miners, the City, and the residents were in trouble.

By 1852 however, there were by now a significant group of residents who were hoping to "make their pile" by starting businesses and making San Francisco their permanent home but they were stymied by the city's lack of infrastructure and organization. The City was definitely feeling growing pains. Its problems included:

- It had an extremely diverse, unskilled, and unreliable population — that would leave whenever news of a gold strike was heard.

- Its economy was completely reliant on the manufacture and export of gold — a source of capital that fluctuated wildly.

- And it desperately needed supplies. If one needed a new pair of pants, building materials to make a house, or sugar for one's coffee, it had to be imported from the Eastern states, South America or Hawaii. Most goods were imported and there was a real feeling starting to grow that California should take advantage of its natural resources.

- There was no organized workforce to help get industry off the ground but there were rumblings of discontent among this group because of license taxes that were imposed upon people who produced or manufactured things. This coupled with the general sentiment that mechanics and laborers weren't paid a living wage meant that something had to change.

Meanwhile, the newspapers of the day abounded with stories of Mechanics' Institutes around the world and how they helped their communities prevail.

The mechanics of this city began to see the need for such an organization — one that catered to their socio-political needs, their reading interests, and their professional growth.

On the evening of December 11, 1854, John Sime, Roderick Matheson, Benjamin Heywood, George Gluyas and a score of others assembled in the tax collector's office, at City Hall with the object of forming a Mechanics' Institute. They all shared similar dreams: boundless faith in the future of San Francisco as a port and industrial center, concern about the moral atmosphere of San Francisco, and most importantly they had an intense aversion of imported goods, which they believed kept prices high and deprived local people of jobs.

From the beginning the directors knew what sort of Institution they wanted:

- A library with open stacks so all the books were accessible to the members.

- A game room where members could spread out their chess and checker boards.

- Classes that would stretch the mind and teach new skills

- To be an organization that welcomed everyone regardless of race or gender

- and to cost as little as possible.

The Constitution and By Laws were shortly written and a logo was designed by architect Thomas Boyd

Funding

Prior to the Rogers Act of 1878, there was no mechanism in place to fund libraries in California, thus all had the challenge of finding a reliable funding source. The Mechanics' Institute was designed, like most other "public" libraries of the day, to be a stock company with two types of membership: stockholders who purchased shares worth $25 each with 10% due at signing and $1.50 payable quarterly in advance; and subscribers who paid an initiation fee of $5 and $1.50 quarterly. Subscribers had all the privileges of stockholders except for the right to vote and hold office. This plan, if effective, would have resulted in $75,000 in capital with which the Institute could purchase a lot, construct a building, and fit out its library.

The stockholder system was never successful. The Mechanics' Institute had difficulty getting its stockholders to pay for the stocks they had promised to buy (only 10% was due at the time of purchase). The system would undergo several changes in the coming years and ultimately was abolished in 1869. Today the Institute is funded by membership dues which covers 7–9% of our income. The rest of our funding comes from donations, income generated by the Institute's rental property, and interest on its endowment.

Starting Out (1855–1866)

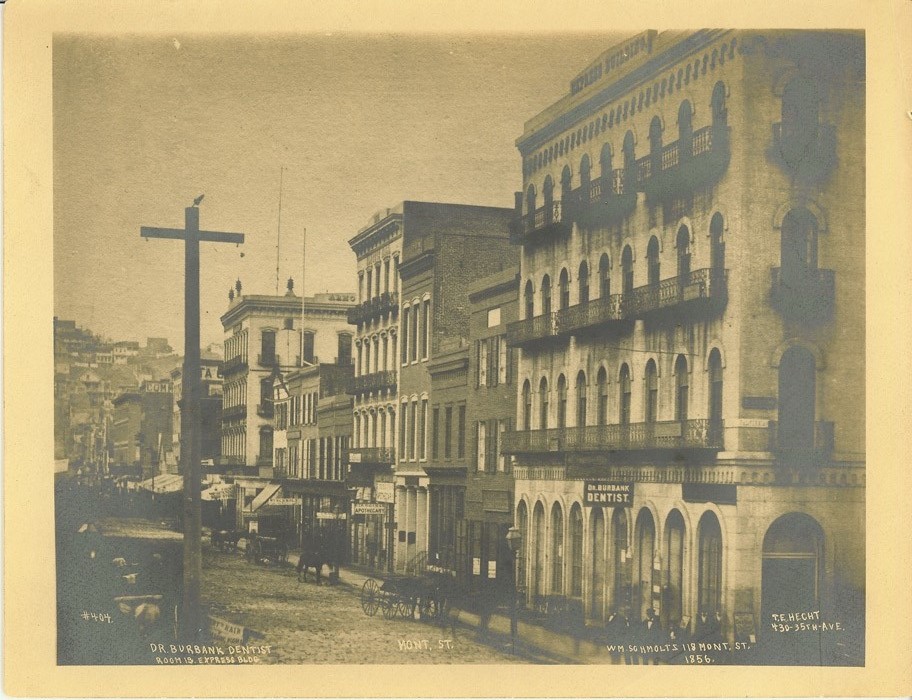

By June 1855 the Institute rented two rooms on the 4th floor of the Express Building which was on Montgomery Street at California. A visitor described our lodgings as being very comfortable with some 400 books and a growing collection of scientific curiosities including samples of California's minerals, petrified Oregon pine, and an eagle's leg and claw of monstrous size[2].

A course of lectures was also planned and on November 2, 1855, Col. Edward Dickenson Baker delivered the first, on the Dignity of Labor at Musical Hall — the largest venue in the City. The newspapers the next morning described it as "one of the largest gatherings ever assembled in California". The future of the Mechanics' indeed looked bright but within the year it became evident that membership dues were not enough to keep the lights on and pay the staff. The Institute's finances were so dire that its librarian, Peter Bartelle Dexter, offered to work for free.

First Fair

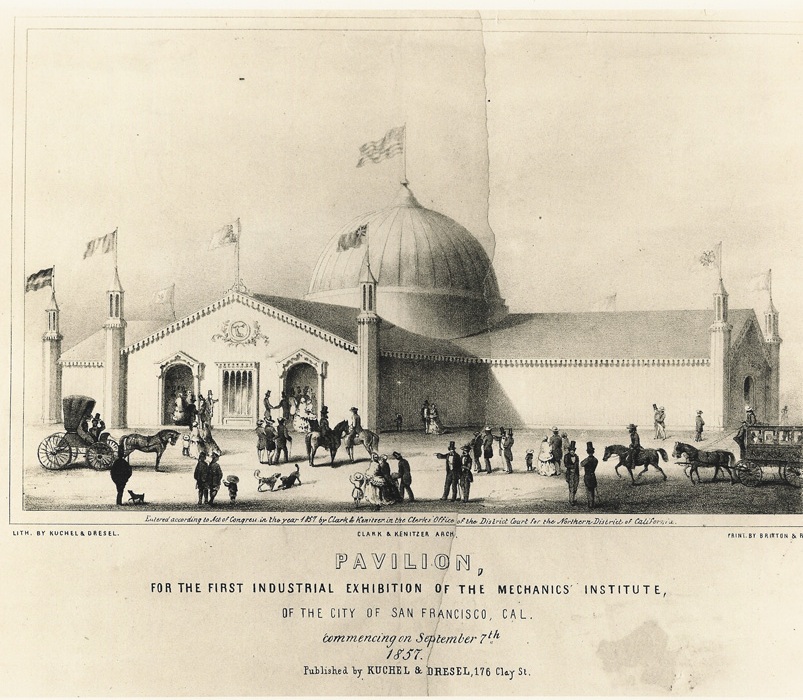

The directors had to come up with a plan so they decided to host an Exposition — like other Mechanics' Institutes did in the eastern United States and Great Britain — to raise money to support the classes offered by the Institute, provide money for the purchase of Library materials, and to promote local industry and agriculture.

Advertisements for the upcoming fair were distributed at post offices, labor exchanges and in newspapers up and down the State advertising the upcoming Exposition and inviting manufacturers, inventors, farmers, miners, and artists to take part. There was no cost for Exhibitors and prizes were to be awarded

By the summer of 1857 the Institute erected a Fair Building on a sandy hill on the outskirts of town — on Montgomery Street between Post and Sutter (where the Crocker Galleria shopping center is now). The wood frame building had a canvas roof and was approximately 18,000 square feet — then the largest building in California. The interior was cross-shaped, with four rooms that opened onto a central lobby. Beneath the dome was a bubbling fountain festooned with flowers and above, hanging from the rafters was a huge eagle with wings outstretched — a symbol of the State's potential.

On display one found an astounding array of the State's natural resources, invention and ingenuity. There were four examples of billiard tables, cabinets filled with curiosities, samples of the state's minerals, a bountiful display of the State's finest flowers, fruits and vegetables; a fire engine, fancy articles such as needlework, fabrics and laces, and art — from the Nahl brothers, William Jewitt, and many others.

The first fair lasted for nearly four weeks and had about 10,000 visitors (roughly 25% of the adult San Francisco population at the time). There were 650 different exhibitors with approximately 25% of them being women. Ultimately there would be 31 fairs between 1857–1899 which would contribute greatly to the economy and industrial pursuits of the San Francisco Bay Area. These fairs, and the rental of the fair buildings, were income generators for the Institute and supported its library and other services.

The Institute at 31 Post Street (1866–1906)

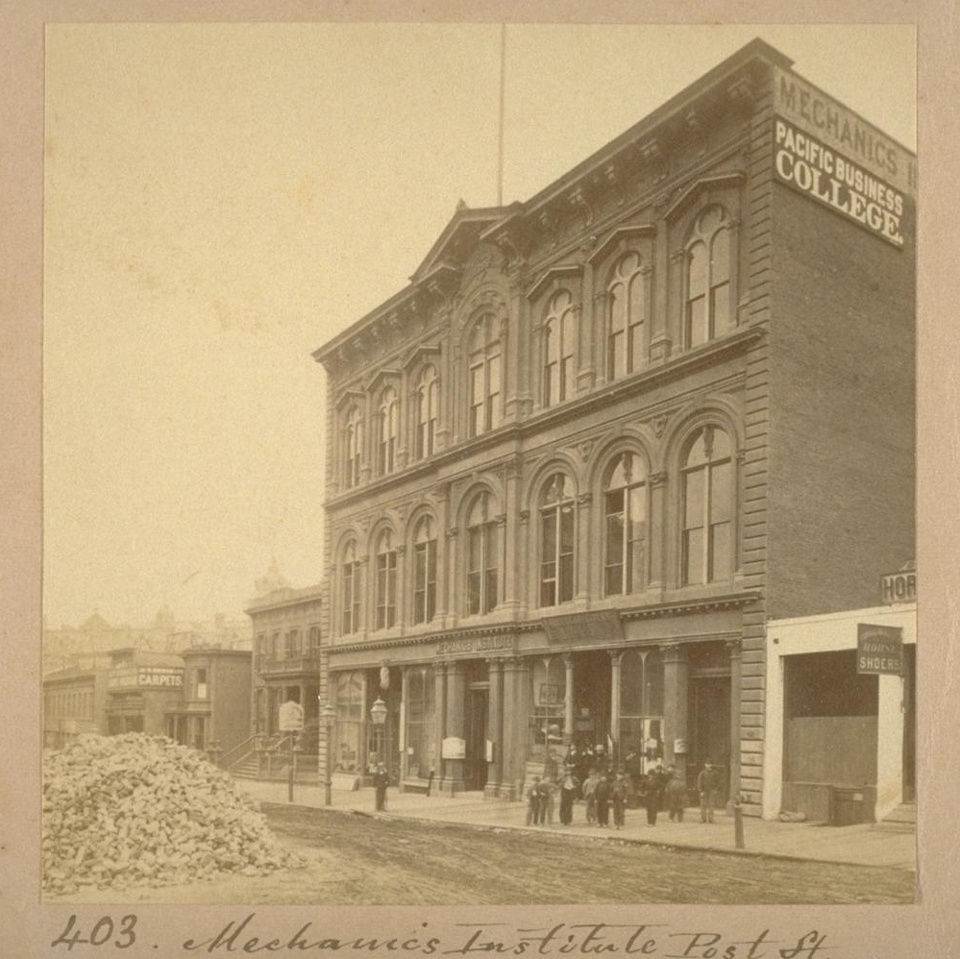

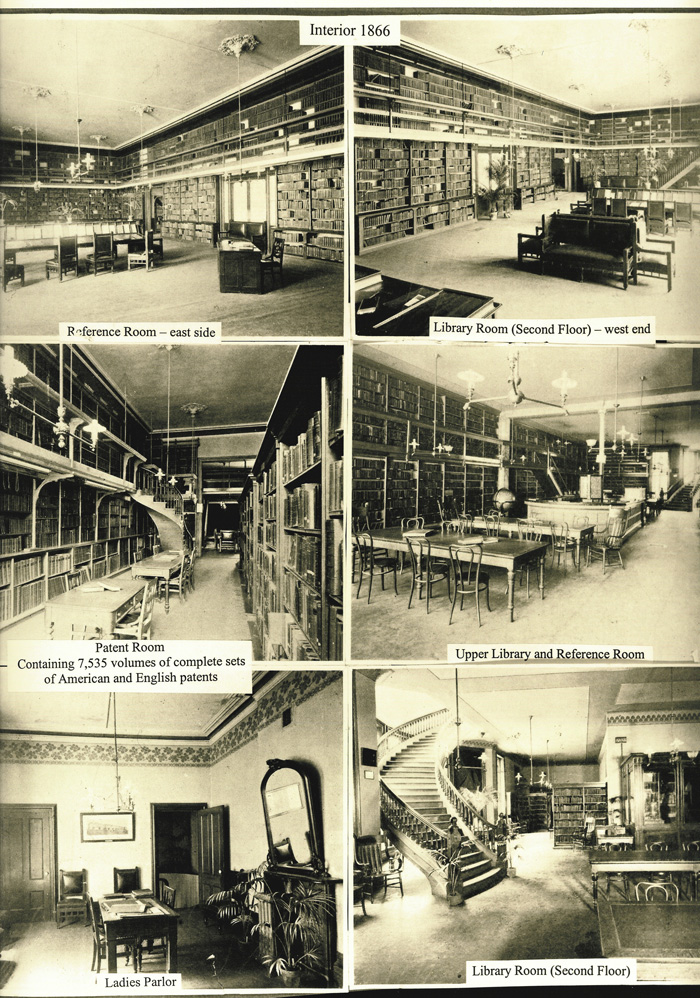

After a rocky first ten years, the Institute finally was financially stable enough to purchase the site of its present home on Post Street, between Montgomery and Kearny in 1866 and erect a three-story building that was designed by William Patton. The new building featured retail spaces on the ground floor, a spacious, well lighted and well ventilated library with open stacks; a lecture hall for about six hundred people, a commodious chess room, a handsomely furnished ladies sitting room, and many other rooms slated for rental by committees, lodges, and related scientific organizations[3].

The Institute quickly became a cultural center of the City hosting free lectures on science and technology, technical classes in mechanical drawing, applied mathematics, wood carving, iron work and other technical subjects. Its rentable meeting rooms were available for tenants to host soirees, literary readings, and socio-political discussions. These auxiliary activities show a fascinating side of the Mechanics' Institute and were a reflection of the popular issues of the day.

Relationship with UC Berkeley

The Institute's important in California technical education reached its pinnacle in 1868 when the California Legislature granted a charter for the establishment of the University of California. The Institute's President was tapped by the Governor to serve in an ex-officio capacity on the Board of Regents. The Institute heavily participated in the fledgling University's first years, hosting technical classes and lectures in its rooms on 31 Post Street, helping develop the curriculum and sitting on the Board of Regents until 1974.

Earthquake

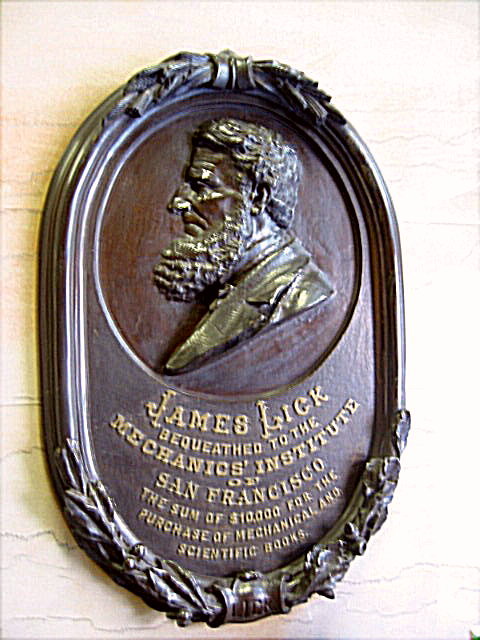

At the beginning of 1906, the Institute had 4,150 members and 135,000 volumes. In January that year, it absorbed the collections of art, literature and rare editions held by the Mercantile Association, another independent library that was founded in 1852. This union formed a magnificent collection amounting to some 200,000 books. When San Francisco was leveled by the earthquake and fire of April 1906, the collections and building were completely destroyed. The loss included the Institute's priceless files of California newspapers, its complete set of British patent reports dating back to James I of England (1603–1625), its collections of technical, scientific and artistic works, plus its Post Street building and pavilion. The contents of two safes were uninjured. The records saved consisted of about twenty five years' minutes, the members' ledger, some leases and contracts and a few other records, among them the original copy of the Institute's Constitution with signatures of the members. The only thing unharmed in the building was the bronze cast of James Lick

The Institute at 57 Post Street (1906–present)

Memories were all that remained as the result of the earthquake and fire. Its devastation spread to much of the central part of the city. The Mechanics' Institute erected a temporary building at Grove and Polk Streets, where it had bought a block of land in 1881 on which now stands the Civic Auditorium. The Institute's Office opened on May 23, 1906, construction was begun on June 4th, and after many trials of delayed materials and a scarcity of construction workers, the new building opened its doors in August, about four months after the fire.

The first day of the fire, the Head Librarian sent telegrams to libraries and book dealers in the Eastern states, requesting books for the collection. Books on architecture and engineering were particularly desired. The highest priority for the Library was to obtain everything that could be gotten on architecture, building construction, and engineering, in fact everything that would be necessary or useful to aid in rebuilding the City. The trustees authorized that $5,000 be spent at once on the purchase of books. The opening collection of some 5,000 books quickly grew to over 17,000 volumes. There was fear that the Institute would soon be confronted with the ever-present problem at the former 31 Post Street location... how to find more room. By August, the Institute had lost nearly 1,000 members. Some had left the city, while others found the new location inconvenient. In fact, there was some doubt whether the former Post Street location would be the best spot to rebuild the Institute building. Some felt that the Institute should move a little further west, since the shopping district had moved a few blocks west of its old location.

Hired Albert Pissis

By July 1910, the new nine-story building at 57 Post Street was completed and on July 15, the Institute moved into it. By 1912, collections totaled some 40,000 books. That same year, San Francisco decided by popular vote to establish a Civic Center. The City bought the Institute pavilion block for $700,000. At the Institute's 1914 annual meeting, the constitution was amended whereby the Post Street property, city bonds and other assets together be established as a perpetual endowment. Since that time, the subject coverage of the collections has broadened to meet the interests of an increasingly diverse membership. The resources continued to grow along with the rapid industrial growth of California..

The Mechanics' Institute continues to be a leading cultural center that includes a vibrant library of some 160,000 volumes, a world-renowned chess program and a full calendar of engaging cultural events. The Institute today is a favorite of avid readers, writers, downtown employees, chess players, and the 21st century nomadic worker.

Each month, the Library adds some 300 new items to its collection of some 165,000 items.

[1] For more information on mechanics' institutes, a seminal work is George Birkbeck: Pioneer of Adult Education by Thomas Kelly, Liverpool at the University Press, 1957.

[2] "Mechanics' Institute of San Francisco", California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences, 14 December 1855

[3] Inagurations of the Mechanics' Institute", San Francisco Bulletin, 27 March 1867.

[4] "Dramatic Affairs", The Californian, April 6, 1867, volume 6, no 20, page 5.

[5] "Amusements", Daily Alta California, 11 November 1870.